I’ve been thinking this week about my recent trip to Shenandoah National Park, when I couldn’t resist taking a picture of one of most recognizable icons of the Park, Old Rag Mountain. I wondered why it is that we can’t resist taking and making pictures of iconic subjects.

Old Rag Mountain is certainly iconic to anyone from northern Virginia who has visited the Park. It appears from several turnouts along Skyline Drive, and it also appears prominently from the roads down in the valley in Madison County, Virginia. Unlike many of the peaks that sit in this part of the Blue Ridge, Old Rag is a solitary old thing, making it easy to identify. Kinda like the big dipper. For many of us northern Virginians, the profile of Old Rag symbolizes all that is beautiful about Shenandoah NP.

The 3300 foot summit of Old Rag is known as a great hiking destination. If you live in northern Virginia, you may have made this hike at some point; millions of people have. For many Virginians, the hike up Old Rag is an annual pilgrimage. It’s a popular hike for young couples who, apparently, are testing the mettle of each other. Those who make it to the top together, I guess, get to take their relationship to the next level. Apparently. And people have even asked to be buried on Old Rag, according to a good friend of mine.

Because of our feelings for Old Rag Mountain, you’ll find lots of pictures of her on the internet.

Natural icons like Old Rag rarely excite me as a landscape photographer. I have only a few iconic subjects in my portfolio, like Purple Mountains Majesty (Grand Teton NP) and Yellowstone Drama(Yellowstone NP).

By definition, taking a picture of an iconic subject means that you’re not the first to do so. In fact, the more iconic the subject is, the more it’s had its picture taken. Who hasn’t seen the hundreds of variations of Ansel Adams’s picture of the Snake River? It’s an iconic scene. But today any picture from the same vantage point is also common, cliche, and even boring at this point. But still, if you’ve ever been to this vista over the Snake River valley and didn’t take a picture of it, well, you’re the exception to the rule 🙂

By definition, taking a picture of an iconic subject means that you’re not the first to do so. In fact, the more iconic the subject is, the more it’s had its picture taken. Who hasn’t seen the hundreds of variations of Ansel Adams’s picture of the Snake River? It’s an iconic scene. But today any picture from the same vantage point is also common, cliche, and even boring at this point. But still, if you’ve ever been to this vista over the Snake River valley and didn’t take a picture of it, well, you’re the exception to the rule 🙂

Driving up and down Skyline Drive on my many trips to Shenandoah NP, I’ve probably passed Old Rag Mountain hundreds of times. Until my most recent trip, never have I stopped to take her picture. I didn’t feel I had anything new to say about her. I don’t want to be boring.

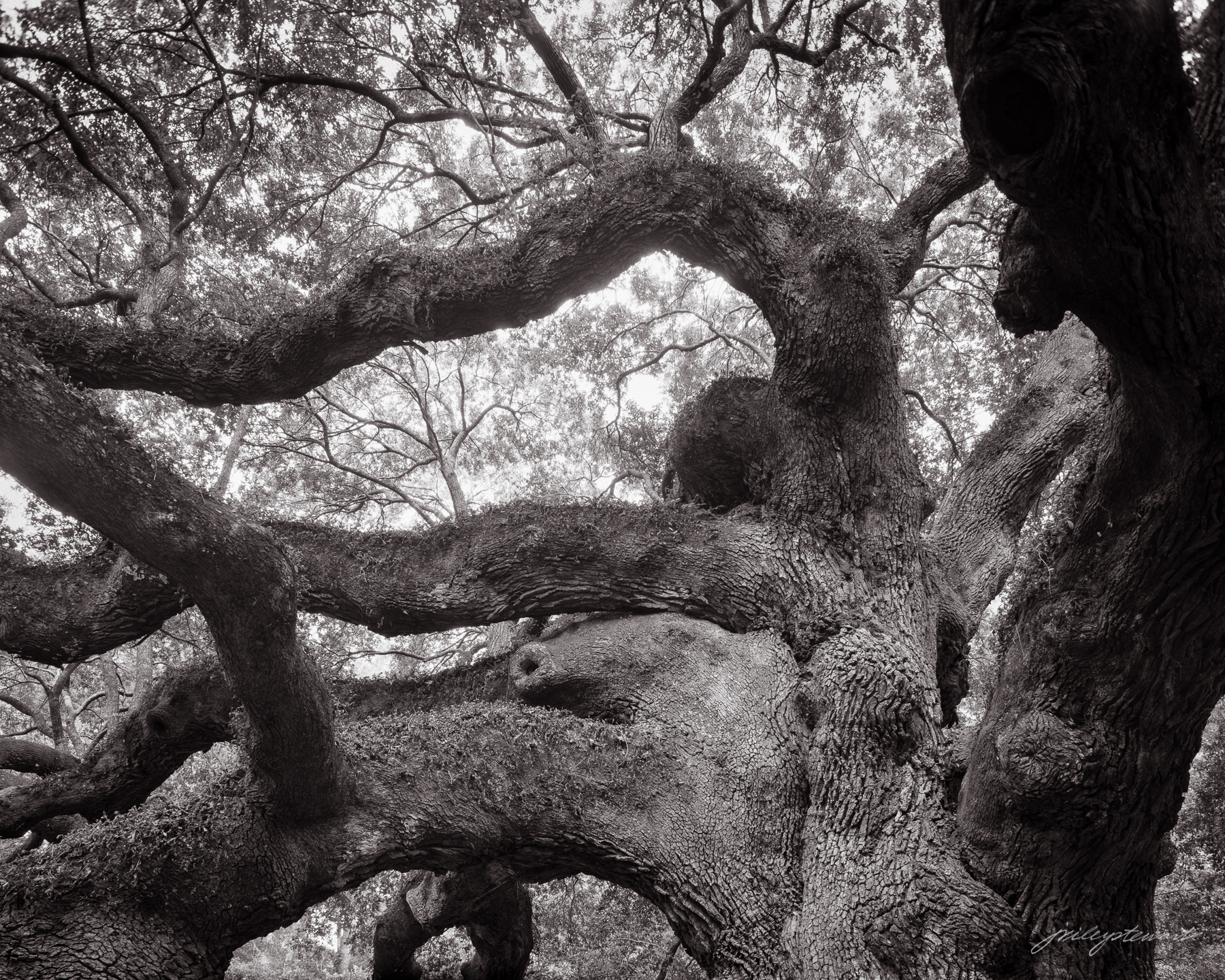

On my most recent trip, I witnessed a rare face to iconic Old Rag, and I knew I had to share it with you. I found this moment to be quietly dramatic, with heavy foreboding clouds and rain storm, and with the forest all wet and dark, but through it all, Old Rag catching the proverbial silver lining.

Pictures of icons like Old Rag Mountain are important to us. They remind us of important experiences and make us nostalgic about those moments. And the fact that a mere image can do that for us is nothing short of amazing. And that’s what I love about photography!

Before leaving, I wanted to ask if you’ve seen the trailer to my new book “At Water’s Edge?” If you’re interested in helping me support the children under the care of the Marland Children’s Home in Ponca City, OK, you can order the book directly from Blurb. Thank you in advance!

Until next time,

J.

PS. Clicking the image of “Passing Storm, Old Rag Mountain” will take you to its place in the gallery, where you can explore the details and see how it might give you just the right place to go when you need a bit of quiet drama.

Did you enjoy this edition of Friday Foto? Feel free to share this email with someone you think might also enjoy it, and invite them to subscribe to “Under the Darkcloth.” And please leave me a comment or ask a question by replying to this email.

Copyright J. Riley Stewart, 2018, all rights reserved.

In the meantime, if you want to connect with me on Instagram just click the Instagram button in the footer of this email and follow along. I’ll do the same for you. I’m doing my best to post a photo-of-the-day, and having a lot of fun seeing what my instagrammers are up to.

In the meantime, if you want to connect with me on Instagram just click the Instagram button in the footer of this email and follow along. I’ll do the same for you. I’m doing my best to post a photo-of-the-day, and having a lot of fun seeing what my instagrammers are up to.