What happens when artistic license is applied to a photograph intended to make us believe a moment actually took place? What happens when the power of photography is used to compel people to believe something happened, when in fact the moment / event never happened?

I watched a video by Hiroshi Sugimoto this morning about his collection of fossils, and it got me thinking about his belief that fossils and photographs are similar in that both are “time-recording” devices.

Fossils show us a likeness of something that lived millions of years ago. We can see the skeletal impressions of fine bones, and holes where eyes once were, and sometimes even the bones of what it had for dinner, resting forever in what once was an intestinal tract. Fossils are a documentary record of what actually was, at some moment in history.

Upon its invention in 1839, photography became yet another tool for humanity to document history, no less important than the archaeological record. Just as a physical object (like a fish) under pressure created the fossiles, the presence of light reflecting off a physical object could create a photograph, and thus document a real moment in time that fractions of a second later became history.

This is one of the aspects of photography that absolutely fascinates me. It’s ability to capture a moment in time; unique moments that would otherwise be lost forever as our brains quickly dismiss them in an attempt to rapidly process millions of other visual inputs. The realism of a photograph is what makes it so powerful as a ‘time-recording’ device.

People of my generation tend to believe the photographic image. We’ve grown up believing that photographs are a true facsimile of some event, some moment, that actually happened. Simply because most photographs we’ve seen throughout most of our lives were exactly that. While photographs may have been artfully modified to reflect the photographer’s vision (versus the camera’s), there was no doubt that the images were likenesses of something real at a specific moment in time. We didn’t question whether Ansel Adams’s mountains and rivers, or clouds, or cacti were real.

Now to be clear, artistic photography has always had an element of the ‘unreal’ behind it– we call it artistic license. Paintings, illustrations, and even doodles on a notecard are entirely contrivances of the human imagination and depend wholly on artistic license. We accept artistic license in art photography as being okay, because art in any form is intended to make us FEEL, and less so to make us believe.

Unlike art photography, documentary photography is primarily intended to make us BELIEVE, and less so to make us feel. Photojournalism is a great example. A news photograph of an event is intended to make us BELIEVE the event happened, and secondarily to make us mad, or happy, or just make us feel well-informed.

What then happens when artistic license is applied to a photograph intended to make us believe a moment actually took place? What happens when the power of photography is used to compel people to believe something happened, when in fact the moment / event never happened?

It’s so easy to do, especially in the emerging age of artificial intelligence and sophisticated imaging software. Photoshop a 93 year old grandmother in her wheelchair to make it appear as if she’s sitting at the top of Mt Everest. Or two world leaders made to appear to be shaking hands (or throwing punches at each other), even though they’ve never met. Or maybe a small child crying at the feet of a large man. Are these “photographs” real, or are they merely contrivances of the human imagination?

Once photographers–and those who use photographs–hijack the power of photography to knowingly make a false narrative intended to make us believe something that isn’t true, then the power of photography as a believable “time-recording” medium will be lost forever. The intent of a photographer will no longer matter, whether it’s to make us BELIEVE or to FEEL, because we will no longer believe in the intrinsic truth of photographs. All photographs will be viewed with suspicion, as “fake,” as “photoshopped.”

A Prediction: Future generations will likely believe any photograph to be a mere contrivance of human imagination, no more significant than doodles on a notecard.

I fear that’s the direction documentary photography is going, and it disturbs me, no less so than any form of falsehood or dis-information does. No one likes to feel manipulated by someone else, so when someone shows me a photograph and tells me it’s real (i.e., documentary) when it’s anything but, purely to dis-inform me and modify my belief in reality, that person will lose my trust. And I will also mistrust the gimmick he or she used to try to dis-inform me. Who in their right mind actually trusts a magician’s top hat?

Once we as a culture begin using the power of photography (specifically its power of believability) to propagate dis-information, it is certain that we will cease to believe in photographs as a facsimile of some real moment in time. The validity of the so-called “photographic record” will cease to exist. Photographers may just as well be doodling.

Perhaps we’re already at that point in the history of photography. Are we?

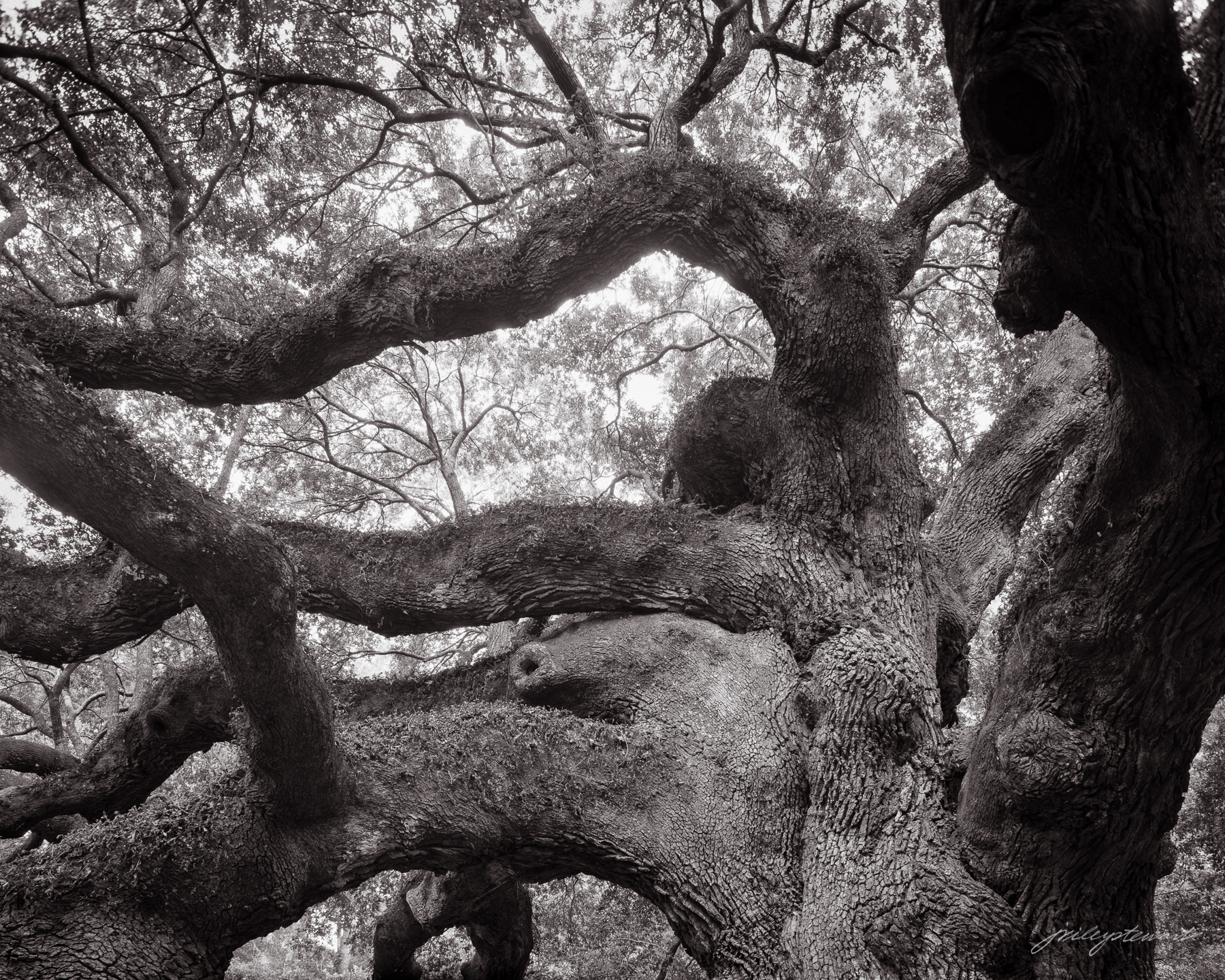

I still consider photography to be a “time-recording” device. As long as I wield a camera and make photographs, I will never make a fool of myself by trying to fool those who see them. My photographs all represent a real moment in time–each pixel or grain of silver, and each dot on the page was created by light reflected or emitted by a physical object that was part of the composition when I took the picture–unless I say otherwise–and even then I won’t refer to it as a photograph. Because it would be something entirely different.

How do you feel about this? Do you believe photography should be true to its power as a “time-recording” device or not? Or is it just me and Sugimoto?

Until next time,

J.

PS: Clicking on “Whisper of a Sunrise” will take you to its place in my online gallery, where you can see in more detail all the splendor of this unique moment in time in the Appalachian Mountains.

For example, if you’ve never seen a fishing fly, you have no way to describe this “thing.” That tuft of feathers on a curvy thingy may be quite confusing to you. But show you that same fly in the mouth of a fish, and it becomes more clear what it is and what it’s supposed to do.

For example, if you’ve never seen a fishing fly, you have no way to describe this “thing.” That tuft of feathers on a curvy thingy may be quite confusing to you. But show you that same fly in the mouth of a fish, and it becomes more clear what it is and what it’s supposed to do.