So, should visual artists try to explain their creations, or just let them speak for themselves?

Recently I read an article by Neal Rantoul, who writes for Luminous Landscape. The title of the article was “A Disturbing Trend.”

What did he find ‘disturbing?” That young photographers today typically include written narratives along with their photographs. He made other points, but this is the one I want to talk about today.

He blames this trend to narrate photographic images on what’s being taught in MFA courses, and finds it inferior to when he was an emerging art photographer. In his day, photographers would exhibit single photographs on a wall or in portfolios or books–usually titled but nothing more–and let the images “speak for themselves.” Rantoul believes that the old way was better, because each viewer of an image could study the image without interference and develop his/her own interpretation, and thus realize a more fulfilling experience.

I don’t have an MFA (that’s a Master of Fine Arts degree). In fact, I have no formal schooling in photography or the arts at all. But that doesn’t mean I have no opinions about what makes a photograph engaging, interesting, and moving.

On this matter, I agree with the youngsters. When I can, I like to include at least an inkling of the backstory or concept behind each of my photographs. I do this not to inflict my artistic intent on anyone, but only to help explain why I thought it was important to make the picture in the first place.

There’s a consistent reason why I choose to make a photograph. It’s because I want to remember the subject or moment–or more importantly a question or idea that strikes me upon experiencing the subject or moment. The questioning and remembering is a huge part of why I’m a photographer in the first place.

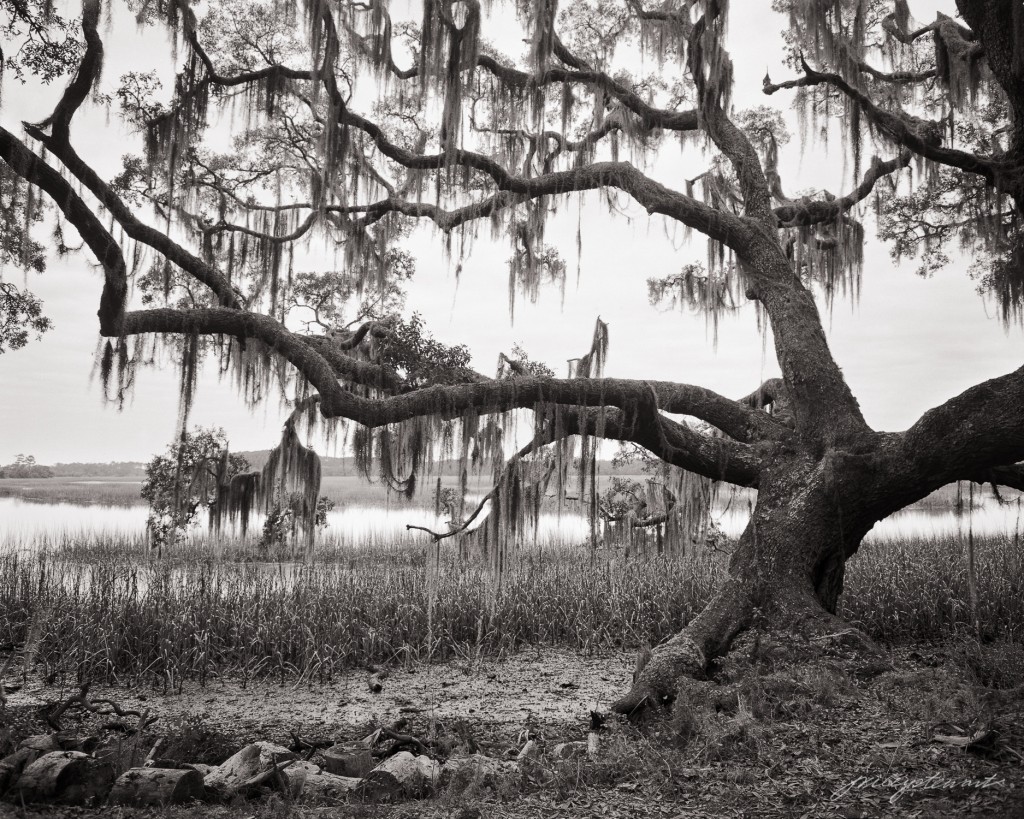

Anyone can make a picture of a tree, whether a photographer, painter, or illustrator. And we may or may not enjoy it. That’s entirely up to each of us. But I think most people will better appreciate and remember the picture when the artist communicates their intent. Sometimes, even often, that intent can be communicated in the title alone, and that’s okay.

Left unsaid, I sometimes wonder why a picture was made in the first place, or even if the artist had any purpose at all in making the picture. And if I find myself wondering why a picture was made, then that means I’m not engaging the picture but instead I’m engaging the artist, and I’ll probably not remember either. The experience is far too fleeting to remember.

I appreciate it when other artists provide a short narrative about why they made a picture; I’m truly interested. An interesting title or narrative starts my mental process of engaging with the picture myself. Only after I consider the picture can I begin to appreciate it. And remember it.

So if a simple narrative starts my mental process going, that’s a good thing for the sake of the art and for me as a consumer of the art.

Unlike Rantoul, I don’t think photographic narratives compromise a viewer’s ability to imagine things for themselves. Art lovers are imaginative folks, and no matter what the artist says regarding his/her intent in making the picture, an art lover, when sufficiently interested in the picture, will take it another step, or in another direction, or embellish it altogether with their own emotions and feelings. When that happens, they will remember it, and perhaps grow to love it, and isn’t that what art is all about?

What do you think? Are you at all interested in what the artist has to say about a work of art that he/she created? Do you appreciate knowing what was in their head at the time? Or would you rather just see the image and make up your own story? Let me know by replying to this email; I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Until next time,

J. Riley

P.S. Clicking on “Just Enough Dirt” will take you to its place in my gallery, where you can explore it (and its tenacity) in detail.

Chiaroscuro is an old fashion style of art, dating from the 1700s masters of portrait, still life, and genre painters like Caravaggio and Rembrandt. But it’s popularity has never gone away. Thomas Cole, Thomas Moran, and Albert Bierstadt, painters from the Hudson Valley School (1800s) extended the chiaroscuro style to landscapes. There are many contemporary painters and photographers who continue to make images in the chiaroscuro style, including me.

Chiaroscuro is an old fashion style of art, dating from the 1700s masters of portrait, still life, and genre painters like Caravaggio and Rembrandt. But it’s popularity has never gone away. Thomas Cole, Thomas Moran, and Albert Bierstadt, painters from the Hudson Valley School (1800s) extended the chiaroscuro style to landscapes. There are many contemporary painters and photographers who continue to make images in the chiaroscuro style, including me.