Let’s talk about the power of mystery in images and why mystery affects our responses to images.

If you are a serious student of art, you’ve undoubtedly read many tutorials about how to use the principles of composition, lighting, and timing to create more interesting images. We all want our images to be interesting, but what does that mean? How do we make our images more interesting; what is it about an image that makes it interesting?

I’ve often watched visitors to art galleries as they browse around the floors. It’s very common to see them roaming around, steadily moving from artwork to artwork, until they stop on a particular piece. Why did they stop on that one? And what is it about that piece that keeps them planted in that same spot well past closing time, I wonder?

I want to deep dive into this topic. It’s intrigued me throughout my study of why some images seem to grab our attention while others do not. It turns out that images that create a sense of mystery can be most engaging, but only up to a point. Ok, let’s prepare to dive.

Our lizard brains love mystery

The science of psychology has lots to say about the role of mystery in the development of modern animal behaviors. I’m going to try to explain, to myself at least, how these theories also help explain one specific behavior in modern humans: why some images trigger a closer look– a worthwhile engagement.

Psychology’s view on mystery is that throughout the evolution of the animal kingdom, a species’ ability to rapidly discern ‘the unknown’ within its environment was critically important to survival of that species. Sounds logical, doesn’t it? Prehistoric rodents wouldn’t have lasted long if they ran wildly into unknown caves, and neither would early man have survived. So the basic skill of heightened awareness to strange encounters in our environment is now something encoded in our DNA, deep in our lizard brains, so to speak.

I guess I already knew that and you probably did too. But something else Psychology tells us is that (and I paraphrase) “Animals are drawn to mystery; they seek mystery. Resolving mysteries is profoundly important to understanding our perceptions (encounters) of what we see (or smell, feel, hear, etc). But before we can resolve mysteries, we must first FIND them. Animal evolution has finely tuned the instinct to constantly seek mysteries in the environment.”

This compulsion to seek out mystery isn’t something we can ignore. Searching for and clarifying strange (mysterious) perceptions is as elementary to our human instinct as socializing and caring for our young. Humans are inherently curious, and we can’t help it.

The obligatory search for mystery isn’t strictly a survival instinct at this point in our evolution. That’s probably not true for every human on the planet, but in general, seeking mysteries has assumed a much less ominous purpose, yet it’s something we still do all the time. “What time is it?” “Is that pot roast seasoned?” “What’s around that corner?” etc, etc. Like I said, seeking mysteries–being curious– is a basic purpose of our lizard brains.

Mystery and human interest are interdependent

Let me share a psychology study I read some years ago and have since lost the reference for, but it’s no less important to the topic. Researchers studied a number of cultures and populations to determine if there is an inherent relationship between a range of novel perceptions (i.e., mysteries) and the interest generated in response to those perceptions.

It happens that humans don’t always find perceptions they encounter to be mysterious. Most encounters are this way; so common and mundane that our lizard brains simply ignore them. Total disinterest.

It’s also true that some perceptions are too mysterious to be believed. Extremely novel encounters can be perceived as ‘unreal’ and therefore unimportant. Again, total disinterest. Consider an image of a square moon, for instance.

The important lesson here is: The level of interest we take in any particular encounter is strongly related to how novel or mysterious we perceive that encounter to be. Too little novelty and our brains recognize the mundane or cliche, and responds with disregard. Too much novelty and our brains respond with a sense of the bizarre, unbelievability, and then immediate disregard.

Between the extremes in novelty is a range of mysteries that generates intrigue and a desire for discovery. Remember, we’re searching for mysteries all the time.

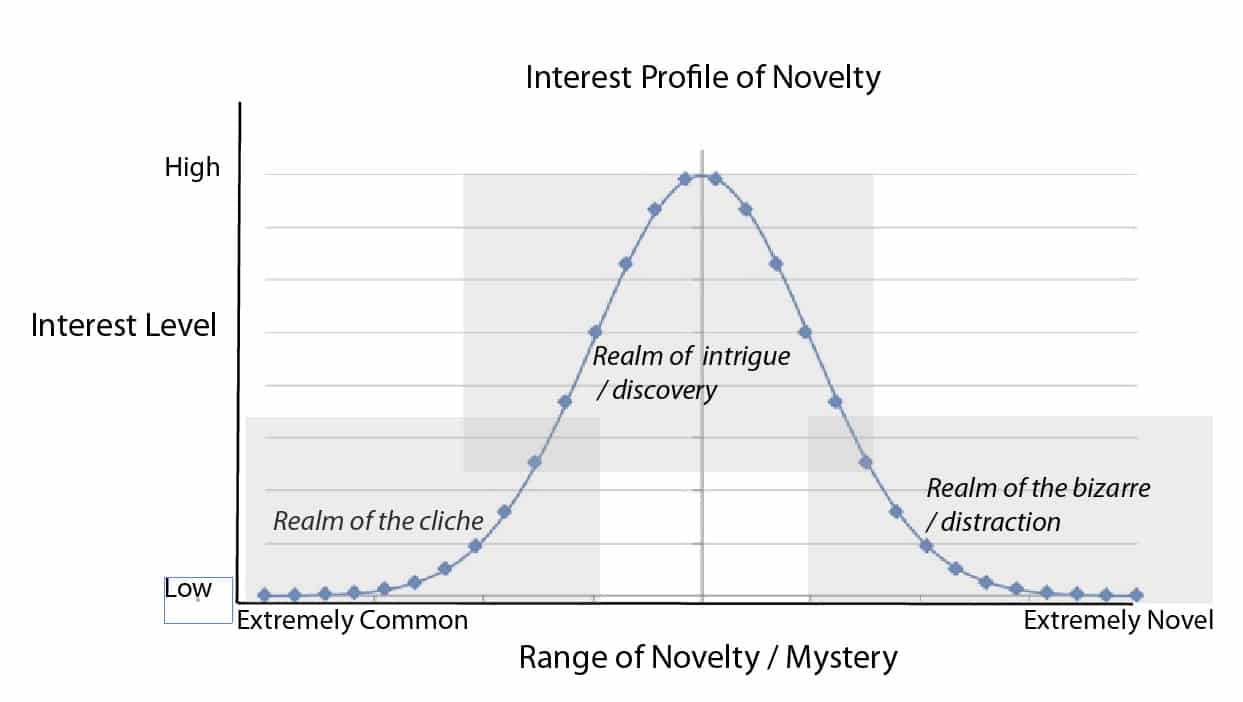

The graph below says the same thing in a different format. Again, I’m recalling the psychology study mentioned above. Clearly, there is a big difference in the interest humans take in a mystery depending on the degree of novelty in that mystery.

This graph is purely notional and not strictly related to time or space. Not all images or visual art styles begin or end as cliche or begin or end as bizarre (although many do, right?). Cliche and bizarre are perceptions, and perceptions change and are very personal.

We can think of the left side of the graph as encounters having no mystery to most people, quickly dismissed by their lizard brains as undeserving of any further interest. The right side of the graph is just the opposite. Encounters over there are so mysterious (to most people) that our brains can’t comprehend the mystery or otherwise judge the encounter to be unreal, and therefore lose interest in trying to resolve the mystery. I used the term “distraction” in the graph, meaning something trivial and undeserving of further attention.

The relationship between novelty and interest shown in the graph is universal to all human populations, but you can’t use it to explain a specific population’s reaction to a specific mystery; it doesn’t work that way. A drawing made by a native in New Guinea may be exceedingly mundane to others in his tribe, but people in my tribe could find that same drawing to be exceedingly mysterious and beautiful. Our interest in things we encounter in our environment (like images) is entirely related to our past encounters, our stored experiences. Well known encounters are perceived by our lizard brains as common and uninteresting. New encounters are perceived as novel / mysterious and our brains treat them differently, until they don’t.

Mystery activates our imaginations

Somewhere between the perceptions of cliche and bizarre sits the realm of mystery that generates (compels) high interest. A little bit of mystery triggers a compulsion to understand the mystery, and in the process of discovery, we call on our imaginations to make sense of the mystery. It is the human imagination that gives mystery its power.

Psychology explains the power of mystery in general to work like this: Perceiving a mystery is a left-brain function. The left brain is where we conduct all our analytical functions, the most rudimentary of which occurs in our so called lizard brain (“What’s that????”). The left brain merely raises the question based on immediate perceptions of what it sees, feels, smells, hears, etc). It communicates the question to the right brain (the creative center) to evaluate the perception and come up with the answer to the mystery (“Don’t worry….it’s only a fly”).

This whole process of immediate perception followed by creative and imaginative resolution is strictly related to the mystery embedded in the perception. If there is no mystery (the left side of the above graph), there is little reason to imagine; the answer is clear already. Done…move on to the next mystery. The whole sequence of such events may take no longer than a few milliseconds.

Well, what happens when the right brain is clueless about what the left brain sent it? Enter the creative process of imagination. First, the right brain compares the perception received from the left brain to its comprehensive database of all known encounters. “It’s a fly.” But, if there’s no explicit match to past encounters (i.e., the experience is novel), the right brain begins to fill in the gaps using imagination. “OK, it’s not a fly”–>”I’ve seen pictures of dragons, and this kinda looks like a dragon.”–> “Yea, it might be a tiny dragon, maybe a (fill in the blank)–>”etc.”

So, a little mystery engages the imagination; more mystery engages more imagination. As long as our brain perceives the mystery as something worth resolving, it will continue trying to resolve it using imagination. This creative process can take hours, days, or even years. And that is a powerful mystery, one that sits somewhere in the upper part of the above graph.

And active imagination is what makes an image engaging

Let’s return to our basic question “why do some images engage us (or compel us) and others do not?”

Certainly, anything that holds our attention can be said to be engaging. The longer it holds our attention, the more engaging it is. Images can do this of course, and in a very powerful way.

I’ll refer to my image “Purple Mountains Majesty” for a minute. If you’ve never seen mountains or have never seen a picture of the Grand Teton Mountain Range, you may perceive what you see in the image as novel and mysterious. You’re left only with your imagination to resolve the mystery underlying the true majesty of the mountains themselves, or the elegant quality of light falling on the scene, or the purity of the refections in the water, or a multitude of other imagined or real elements in the image, and sometimes even beyond the image. To you, the image is an abstraction and perceived as novel and mysterious. Your left brain then engages the imagination center in the right brain to help understand the mysteries you encounter as you explore the image.

“Abstract art” is a common answer to “..what type of art causes your imagination to sore?” And that’s a valid answer; abstract art is consistently among the most popular genre of visual art. Lovers of abstract art explain their love precisely because it engages their imaginations to make sense of the shapes, colors, patterns, or forms present on the canvas. All of that imagining takes time and attention, meaning high interest, engagement, and enjoyment.

But ask someone who dislikes abstract art about it and they’ll give an answer that might sound like abstraction borders on the bizarre, having no interest to them. Unlike the abstract lover, her right brain had no interest in using her imagination to discern what all those shapes, patterns, or colors mean. Mysterious, perhaps, but interesting, no.

The big difference between the abstract lover and her counter is that in the lover, abstraction engages the imagination while in the latter it certainly does not. The whole of the above Interest Profile of Novelty can be explained by the seemingly desperate need for imagination to make an image interesting.

My personal approach for creating mystery in images

I love mystery in my own (and others’) images. In fact, creating mystery is my constant intent, without being cliche and without being anything close to bizarre. My reason for this is not because the graph says to do that, but because those are the types of images I love and love to make.

I’ll cover a few big ways to create mystery. You may have dozens of other ideas. What do you look for in images that create a sense of mystery?

Prominent Shadows, and other forms of obfuscation

I love shadows and find them mysterious. Perhaps you do too. I have a saying that shows up from time to time on my website or in my blog. It goes like this:

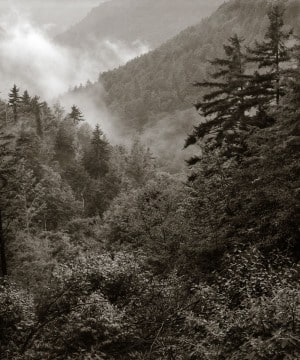

We need light. It provides clarity. But we also need a bit of mystery, and in the shadows we find it.

Featuring dark elegant shadows in images is but one way to convey a sense of obfuscation and mystery. Obfuscation, or hiding things from clear view, confuses our lizard brains and causes our creative brains to solve the mystery. Obfuscation in all its forms can be very engaging. Other ways to create obfuscation include throwing important elements out of focus, hiding elements behind a veil of weather, smoke, or digital textures or even hiding parts of elements behind other elements. These artistic techniques force our imaginations to try to clarify the obscured elements, and in the process, keep our imaginations churning.

American photographer Keith Carter is a master at creating obfuscation in his images. Take a look at his work.

My first awareness of how beautiful and intriguing art can be was when I was in middle school and stumbled upon the romantic works of the Hudson River School masters. They started the American Luminism movement that we recognize today as bright, reflective scenes of sublime nature, often having almost secret, hidden elements of humanity engaged in activities of the day. I loved the sense of light in those scenes, but it wasn’t until I was much older that I realized that it was the subjects hidden in the shadows that really intrigued me and kept me engaged in the images.

Those early images inspire me to use shadow and light in much the same way in my images. While there are many ways to create obfuscation and mystery in images, the use of elegant shadows is very effective. When I say “elegant shadows”, I mean deep tones having details, not solid black areas that have no meaning or intrigue. There is nothing mysterious about pure black.

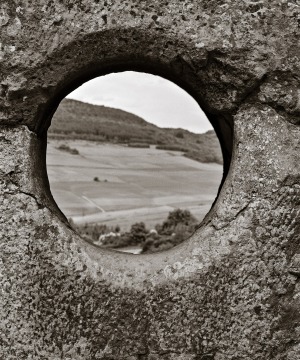

Here’s a few examples of how I use dominant, elegant shadows in my work, from my Romantic Landscapes collection.

Intriguing Subjects

Certain subjects are inherently mysterious to most Americans. Old castle ruins are wholly unknown through first hand experience, but we recognize them as ancient, rare, and sublime. They can possess immense mystery and trigger our imaginations to conjure up visions of life in the middle ages.

I lived in Germany for almost 3 years back in the 1980s. I was lucky to get to spend many hours crawling around old castle ruins while there. I found myself alone on many of these visits, which gave me lots of time to consider the hidden, mysterious stories that only the stones could tell.

There are many, many other subjects that are commonly perceived to be mysterious, like towering mountains, crashing ocean waves, and perhaps even spiders and snakes to some. Here’s a few of my mysterious castle images that come from my Timeless Walls collection.

Novel situations or moments

We all love images of stranger things. They can be highly mysterious and interesting. Examples include strange relationships among natural (or unnatural) objects or rare environmental conditions: Night. Fog. Severe weather. Scary? Mysterious? Yea.

Uncommon moments aren’t as uncommon as much as they are uncommonly photographed. Consider underwater images, or images of the deep galaxies. Or perhaps the capture of a gazelle by a jaguar. These situations happen all the time, but rarely photographed. But that still makes them uncommon and therefore mysterious.

As a landscape photographer, I’m always searching for weather, lighting, or seasonal situations that depart from my everyday experiences, precisely because I enjoy the mystery in them.

Shock and Awe

As a photographer, I love seeing others’ photographs. It seems to me that over the last decade or so, there’s been a growing intent to create a sense of ‘shock and awe’ in our imagery. As if by creating unimaginable images, we can grab attention of more people, and that results in greater engagement and greater rewards to the creator of those images.

Let’s talk about the value of ‘shock and awe’ in imagery, especially in photography. Can it be mysterious? Certainly. Perception of mystery is a popular response to images that appear to be “out of this world.” They definitely encourage imagination and (sometimes) gullibility. My personal feeling is that painters and illustrators can get by with a lot more shock and awe than can photographers, because photographs remain generally accepted as ‘coming from reality’ while paintings and illustrations are not.

When done honestly, photographs of unimaginably exotic places and moments can be highly mysterious. I find the most intriguing images in the ‘shock and awe’ category are those that are honest photographs of real subjects and real stories that clearly stimulate the imagination. There are many, and I admire the works of photographers who go to great lengths to show them to us.

And, I suppose, so can hyper-saturated photographs containing unreal colors or super-imposed subjects masquerading as reality be mysterious. To me, such images tend to fall on the right side of Novelty: Interest relationship curve. The more gaudy and unbelievable they are, the farther down the slope they go, to a point where I and most people would consider them to be bizarre, and not in an interesting way. But who knows, perceptions are highly personal.

I try to be authentic in my own work. I believe strongly that photography should inform our perceptions of reality. Heavily manipulating photographs for the purpose of creating mystery through shock and awe isn’t something I choose to engage in, because my left brain quickly labels them as ‘bizarre.’

Many other elements of imagery can compel a sense of mystery and cause our brains to jump into imagination mode, at least until they become common and uninteresting. A new presentation method, such as printing images onto highly glossy metal surfaces, can be perceived as new and mysterious and generate high interest. High Dynamic Range (HDR) photography is another example. The advent of vibrant acrylic paints is another. When the first photographs appeared in gallery wraps, that was a definite departure from the traditional, and people still find it to be very interesting and enjoyable way to present wall art. And what about writing captions or poetry within the framing of an image? Pretty interesting at times.

Consider also examples of artists re-introducing methods and presentations once considered archaic and subsequently generating high interest, partly because those presentations had never been seen by modern people. Platinum-palladium printing, or carbon printing, or tin-types, or any number of once-archaic alternative processes in photography are very interesting, initially because we perceive them as novel and let our imaginations fill in the gaps about how they were created.

There is no end of ways to change methods or approaches that cause a sense of mystery and create high interest (or low interest). Photographers are supremely adept at doing this. Feel free to comment and share other ways you’ve seen artists induce novelty to their artworks, and whether you think of them as interesting or not.

Summary

In serious studies of art, we seem to skip over the fundamentals of how we as humans behave when we encounter the range of beauty, inspiration, message, or any host of outcomes often assigned to art appreciation.

In this article, I’ve tried to describe my interpretation of the involuntary psychological connection between mystery and imagination to explain why images compel engagement. Humans, like all animals, constantly seek mystery.

Visual encounters that trigger first a sense of mystery, then imagination to solve that mystery, is as old as humanity itself. Knowing this linkage exists helps us understand why certain images grab our attention and compel us to think about (imagine about) them, often for several minutes or even years. The association between mystery and the imagination also helps us understand why we dismiss common, cliche images and quickly reject bizarre, “unreal” or otherwise extremely novel images.

I go through periods of my art-making when I begin suspecting that my images are too boring, and not worth making anymore. At the same time, I’ve gone back to those images that are more abstract and mysterious, and respond to them in a completely different and more enjoyable way. I think if I can find that zone between too common and too novel, I will eventually get more enjoyment from my image-making. And if I’m able to find that sweet spot, I hope others will too.

J Riley Stewart, 2020

D.V.M, Ph.D., Photographer

For example, if you’ve never seen a fishing fly, you have no way to describe this “thing.” That tuft of feathers on a curvy thingy may be quite confusing to you. But show you that same fly in the mouth of a fish, and it becomes more clear what it is and what it’s supposed to do.

For example, if you’ve never seen a fishing fly, you have no way to describe this “thing.” That tuft of feathers on a curvy thingy may be quite confusing to you. But show you that same fly in the mouth of a fish, and it becomes more clear what it is and what it’s supposed to do.